Note: This is the second installment of a two-part series. You can read Part I here.

When Kyle Serrette learned back in February that Louisiana was on the verge of winning an $8 million charter school grant from U.S. Department of Education, he wasn’t happy about the news.

After all, he had spent the previous six months working to establish the Louisiana Alliance to Reclaim Our Schools (LAROS), a secret group of education leaders dedicated to securing a statewide moratorium on charter schools. Now that LAROS was ready to implement its plan to slow the growth of charters, the federal government was going to give state education officials a pile of money to expand them. Something needed to be done to stop it.

Serrette sent an email to LAROS members asking if anyone had connections inside the Louisiana Department of Education (LDOE) who could tell them whether the grant had been finalized. If the terms were still being negotiated, Serrette wanted the group “to try to stop millions of new dollars from flowing into Louisiana to start lots more charters most likely in cities other than NOLA.”

In response, Louisiana Association of Educators (LAE) president Debbie Meaux immediately reached out to David Shepherd, director of charter development at LDOE, to check on the status of the grant application.

As it turned out, they were too late – the grant was a done deal. Nevertheless, the episode shows that LAROS was willing to use any means necessary to fight charter schools, even if that meant sabotaging a grant that would bring millions of dollars to Louisiana.

LAROS’ Two-Tier Strategy For Fighting Charter Schools

This aggressive, no-holds-barred approach should be familiar to education policy observers. It’s a defining characteristic of the broader anti-charter school campaign being waged by the teachers unions all across the country. The LAROS Papers make clear that the group is not only part of that broader union-driven campaign, but was established primarily to fight charter schools, although its focus expanded to other issues over time.

St. Tammany School Board President Jack Loup has been a member of LAROS since its inception and attended the group’s first meeting in September 2015. In an email to fellow board member Mary Bellisario about the meeting, Loup noted: “This new group is excited about adding groups and individuals to assist in securing a moratorium on Charters [sic].”

However, that excitement was tempered by the political realities LAROS faced in securing a moratorium in Louisiana, where support for charters remains strong and previous proposals to block charter expansion in the legislature have failed to make it out of committee. Recognizing that a direct push for a statewide moratorium would likely end in failure, the group instead developed a two-tier strategy for incrementally building toward that goal by initially focusing their efforts on local school boards.

One part of their strategy is to build support across the state for a moratorium on charters by persuading local school boards to adopt a resolution that LAROS members drafted and revised over several months. Although framed as much-needed accountability and transparency measures for charter schools, minutes from a LAROS meeting last December show that the resolution was intentionally crafted to rob charter schools of the autonomy that allows them to be successful.

That aim is also reflected in the resolution’s endorsement of a series of charter school policies developed by the Annenberg Institute for School Reform, a think-tank at Brown University that has received funding from the national teachers unions. Because the so-called Annenberg standards place onerous restrictions on charter schools that would make it nearly impossible for them to operate, they have been heavily promoted by both the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) and National Education Association (NEA).

Community schools: The Teachers Unions’ Panacea

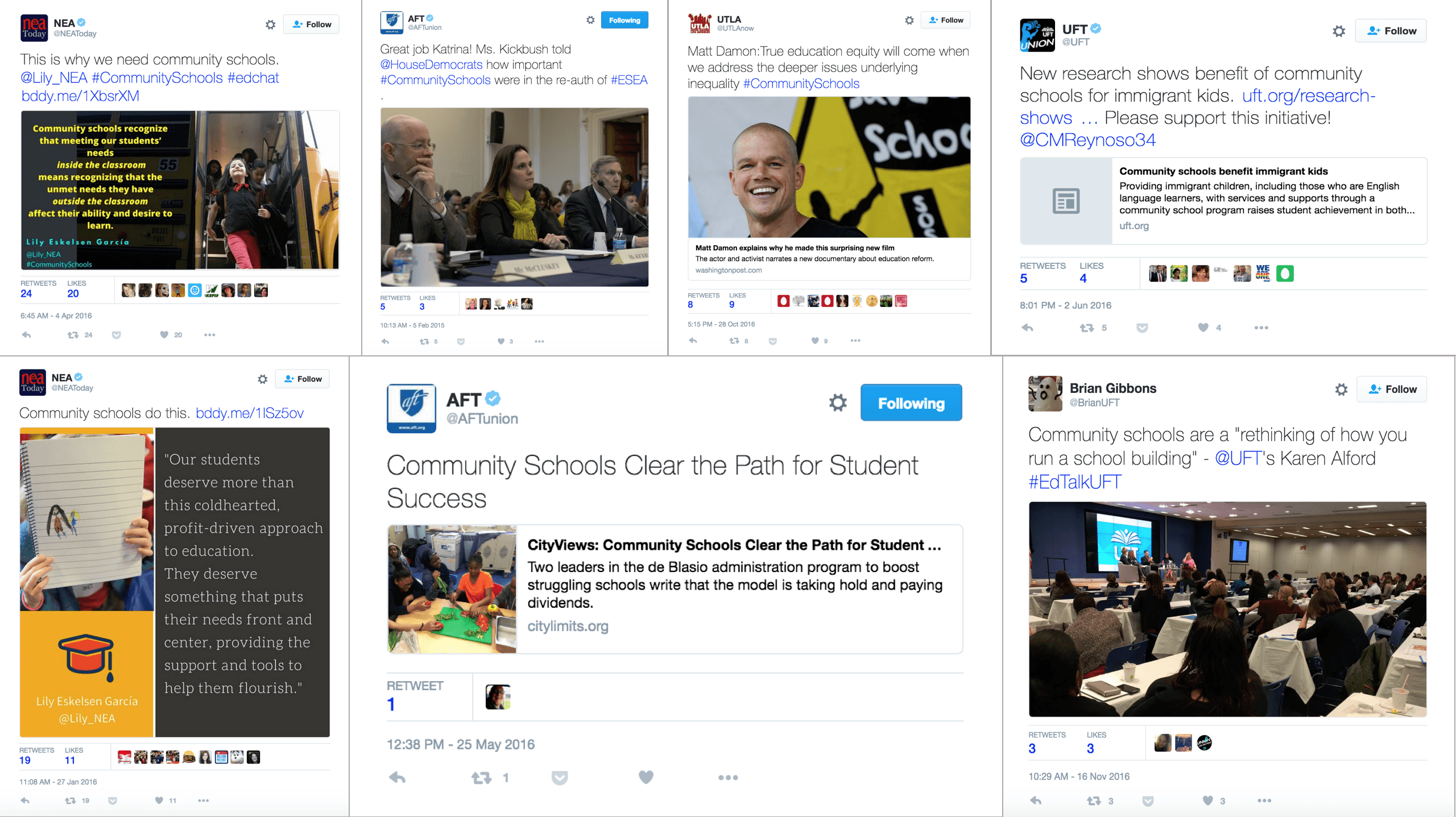

The second, concurrent part of LAROS’ strategy is to convince local school boards to embrace community schools, which they are pushing as an alternative to charters. Community schools are defined as schools with an “integrated focus on academics, youth development, family support, health and social services and community development.” Although nearly all public schools (including charters) provide some wraparound services to students, community schools are intended to be a “one stop shop” for families where they can access things like health care, family resources, counseling, and adult education services all under one roof.

Not surprisingly, AFT and NEA have been heavily promoting community schools as a panacea for all that ills public education since the model neatly aligns with the unions’ “poverty trumps education” argument – i.e., that schools and educators cannot be held accountable for the achievement of low-income children.

Enlarge

But while the model sounds great in theory, real-life examples of high-performing community schools are few and far between. As Center for Reinventing Public Education founder Paul Hill recently pointed out, “Even if wrap-around services improve students’ school readiness, leaders will still be left to address the question of how to make the schools more effective for those students.” Instead, Hill says, the “emphasis on social and health services can lead teachers and principals to think that instructional practices and teaching conditions don’t need to change” and allow community school leaders to “avoid the hard work of managing schools, evaluating instructional staff, seeking and strategically allocating teaching talent, and looking for more effective approaches.”

Plus, community schools are expensive to operate and often require sizable upfront investments to get off the ground, which makes them a tough sell in districts whose budgets are still recovering from cuts imposed during the Great Recession.

Kids in poverty start out with an inherent inequality that no amount of education will be able to fully overcome @Wade4Justice #eseaequity

— AFT (@AFTunion) February 18, 2015

Nevertheless, community schools are a key part of LAROS’ plan. In May, Kyle Serrette held a training for LAROS members in Baton Rouge to finalize their strategies and hone their messages, particularly on community schools.

The group also agreed to initially target “friendly” school boards before moving to places like New Orleans, where school board members would be less receptive to their message. The idea was that their effort would gain momentum across Louisiana as more and more districts adopted anti-charter resolutions and endorsed community schools. Eventually, if all went as planned, LAROS would have enough school boards behind them to push for a statewide moratorium on charters in the legislature.

In fact, it’s clear that LAROS is now in the implementation phase of that plan. Meeting minutes show that the group met with East Baton Rouge Parish administrators – including Superintendent Warren Drake – in August to pitch community schools.

Kyle Serrette also flew down from his home in Washington, DC to proselytize for community schools in meetings with school officials in St. James Parish and even State Superintendent John White.

Moreover, just a few weeks ago, The Advertiser reported that LAROS members Debbie Meaux and Karran Harper Royal, who is being paid by NEA, made a presentation on community schools to the Lafayette Parish School Board.

Of course, Meaux and Royal never mentioned to board members that they were pitching community schools as part of a secret, union-backed plot against charters.

https://t.co/GDyh3O7wQA never ok to shut down a school b/c adults failed kids #nolaed needs #communityschools when biz model fails kids

— Karran Harper Royal (@KHRoyal) December 8, 2016

Shine a light!

It’s so silly that these folks are spending all this time and money to play games instead of working to make schools better for kids.

It appears that the conspiracy theorists had a conspiracy. No wonder they’re convinced of their existence.

@JoeNathan9249 very true! But If these ppl really wanted this to work… they wouldn’t run around in the dark.

I understand that; the most well-known example of the community school approach is Harlem Children’s Zone & its charter-based

I’ve spent 25 years working 4 chartering but also think community schools can be a very good idea. It’s not either or