The Education Research Alliance (ERA) at Tulane University released a new study last week that attempted to gauge how New Orleans principals responded to competition in the city’s supposedly “market-based” public education system.

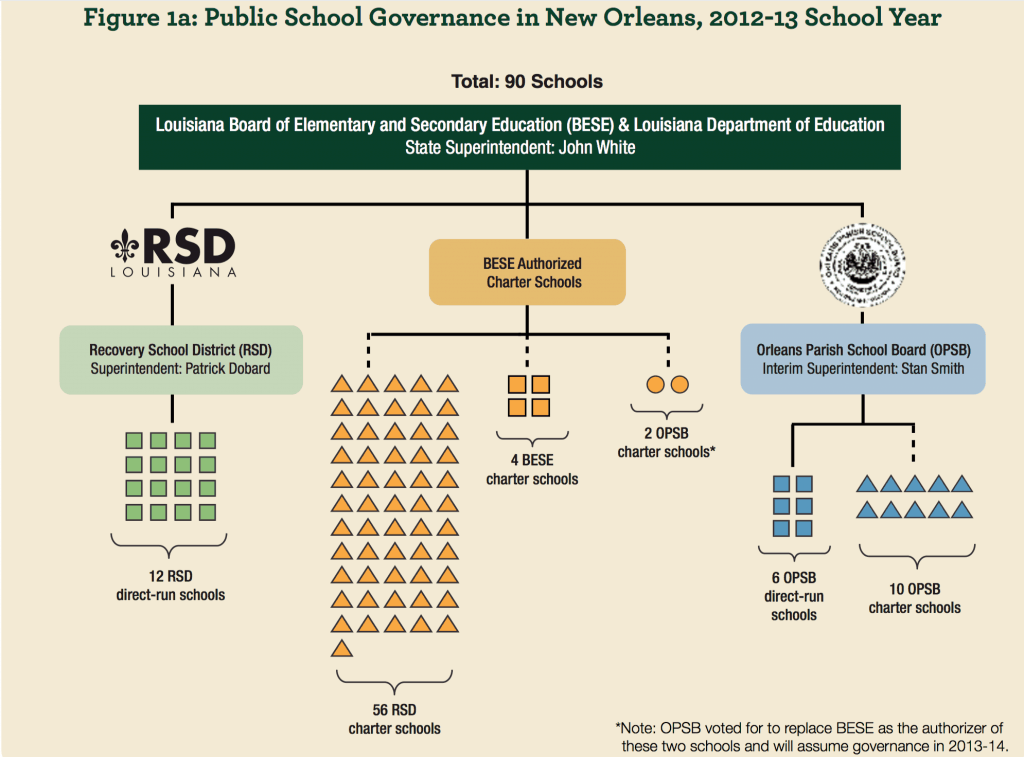

The report – “How Do School Leaders Respond To Competition?” – was authored by Huriya Jabbar, an assistant professor of education policy at the University of Texas at Austin and research associate at ERA. For background, the study [see full report below] is based on a series of interviews she conducted during the 2012-13 school year with school leaders of 30 (out of 90) New Orleans public schools from both the Orleans Parish School Board (OPSB) and Recovery School District (RSD).

While the report generated a lot of attention, here are three questions raised by recent study…

I. Why Did ERA Leave Out The Full Story?

First, let’s address the finding that grabbed all the headlines:

“One-third (10 of 30) of schools selected or excluded students by, for example, counseling students who were not thought to be a good fit to transfer to another school, holding invitation-only events to advertise the school, or not reporting open seats. This number included five OPSB schools and five RSD schools.”

The timing of Jabbar’s interviews is important, because S.Y. 2012-13 marked the first year of OneApp, the city-wide enrollment system managed by the RSD. OneApp was created to simplify the enrollment process by allowing parents to fill out only one application in which they rank schools in order of preference. OneApp then centrally assigns students to each school using a complex algorithm that takes into account those preferences, as well as other factors.

As a result, the advent of OneApp took the enrollment process out of the hands of schools, preventing them from engaging in exactly the types of exclusionary practices mentioned in ERA’s report. For example, because all OneApp schools are linked to a Student Information System managed by the RSD, the district knows exactly how many openings exist at each school and when students are dropped or added to the rolls. Therefore, schools are unable to game the system by underreporting open seats, or illegally dropping students from the rolls.

In addition, there is a very short window for student transfers at the beginning of each school year. After October 1st, students must be approved for a hardship exemption in order to transfer out of their OneApp placement, preventing schools from “counseling out” students. In S.Y. 2013-14, only 156 students transferred during the school year.

Given the concerns raised about possible “creaming” of students by school leaders, one would expect that ERA’s report would take pains to show how dramatically the enrollment process has changed in the intervening three years. In fact, I know that at least one peer-reviewer of the study explicitly and repeatedly urged ERA to provide added context about the changes introduced by OneApp.

Nevertheless, if anything, ERA seemed to downplay the fact that OneApp has made the report’s selection/retention concerns irrelevant. The study’s conclusions are, at times, presented in a way that could leave readers (especially those outside of New Orleans) under the impression that school leaders continue to manipulate enrollment, such as this quote from the policy brief released with the study:

“Without more efforts to manage the current responses to competition like student selection and exclusion, New Orleans could end up with a less equitable school system.”

Furthermore, even when OneApp is mentioned by Jabbar, it’s buried in the report and the efficacy of the system is left an open question:

“For example, central assignment programs, such as OneApp, may help to reduce inequities in access by retaining some central authority over assignment, rather than leaving admissions and lotteries entirely to schools, and removing opportunities to screen and select students.”

Leaving out such an important part of the story is not only misleading to readers, but unfair to educators in New Orleans, especially after ERA was urged to provide a fuller picture about OneApp.

II. Where’s The Beef?

After all of the buildup and fanfare surrounding the release of the Alliance’s past two studies, one might expect the research to be revelatory. But, with all due respect to the folks at ERA, the studies they’ve released thus far have done little more than confirm what we already knew.

ERA’s first report, “What Schools Do Families Want (And Why)?,” found that New Orleans families gave significant weight to factors beyond academic performance when choosing a school. On the other hand, numerous studies of families’ school choice decisions – in New York City, Canada, Beijing, the Midwest, etc. – have basically found the same behavior.

Likewise, Jabbar’s revelation that some school leaders tried to select or exclude students isn’t really news. After all, concern that some New Orleans schools were gaming the student enrollment process was part of the impetus behind creating OneApp in the first place.

In some ways, the rollouts of ERA’s first two reports seem geared toward maximizing attention for the nascent research group than providing a deeper understanding of the transformation of New Orleans’ public schools. The approach seems to be working: ERA’s studies have received garnered a lot of media visibility and ERA’s Director, Doug Harris, just launched a new blog in partnership with Ed Week.

The desire to make a splash is understandable – what’s the point of producing research if no one pays attention to it? However, the absence of context about OneApp, along with some of the more provocative quotes in the latest policy brief (example: “We all want our [student] numbers up so we can get more money, more funding.“) no doubt distort readers’ view of the public education landscape in New Orleans.

III. Why Does ERA Insist New Orleans is a “Market-Based” School System?

I’ve said it. CREDO Director Margaret Raymond has said it. “Market-based reform” is not an accurate description for the type of transformation that has taken place in New Orleans’ public education system since Hurricane Katrina.

It’s true that some charter school advocates – in particular, think tankers on the free market-end of the spectrum – want to portray NOLA’s charter school system as a marketplace where improvement is driven by competition. But, as Michael Stone, co-CEO at New Schools for New Orleans, told The Advocate, “I don’t think I know a single person working in public education in New Orleans who would say that competition for students will drive quality.”

That point seems lost on the folks at ERA, whose research presents New Orleans as the ne plus ultra of a market model. For example, in ERA’s “What Schools Do Families Want (And Why)?,” authors Doug Harris and Matt Larson insist, “no city had ever adopted a comprehensive market school system until New Orleans did in the wake of Hurricane Katrina.” Similarly, in her policy brief on “How Do School Leaders Respond To Competition?,” Huriya Jabbar contends:

”The New Orleans school-choice market, consisting overwhelmingly of open-enrollment charter schools, is arguably the most competitive district ever created in the United States.”

But is it? OneApp offers parents what should be more accurately described as school preference, rather than school choice. Plus, families’ ability to switch schools is limited with the short transfer period. On the the other side of the equation, individual schools can’t simply increase “supply” (i.e., add more seats) to meet demand from parents, given the practical constraints imposed by facilities and staffing.

Furthermore, the RSD’s evolution towards an all-charter district has been guided by a master plan based on enrollment projections and geographical need. At this point, there are few opportunities for charter growth in New Orleans and CMOs have turned their attention to other districts, like Baton Rouge and Memphis, when seeking to expand. Finally, as I’ve noted previously, when schools have closed, it has almost always been a result of accountability policies, rather than under-enrollment due to competition from other schools.

It’s time to move beyond the traditional vs. market-based labels and acknowledge that New Orleans’ public school system is an altogether different animal.

14 Comments

Leave a Reply