“Dozens of employees indicted or convicted on corruption charges. Tens of millions of dollars unaccounted for. Eight superintendents in seven years. Rock-bottom test scores. Shootings, sirens and police uniforms, often. The threat of bankruptcy and bounced checks, constantly.

“In the dismal gallery of failing urban school systems, New Orleans may be the biggest horror of them all.”

– Adam Nossiter, April 2005.

When Adam Nossiter penned this bleak description of New Orleans’ school system, few would have imagined it would be transformed into a nationally-admired model of public education reform.

I know I certainly didn’t. By that time, I had spent two years teaching at John McDonogh Senior High and gone on to support teachers in a dozen schools across New Orleans. The experience left me with little reason to be optimistic. The depth of dysfunction and corruption in the district was simply overwhelming. It was hard to conceive of a way the city’s schools could ever turn themselves around. Ten years later, I am more than happy to admit I was wrong.

For those of us who experienced the abject failure of the old New Orleans Public Schools (NOPS) system, it seems hard to understand why anyone would, as the writer Dawn Roth wrote, “mourn the chaotic, inept, even corrupt system of schools that existed before Katrina.” However, many critics of New Orleans’ school reforms have recently begun resorting to historical revisionism when it comes to NOPS. They seek to downplay the school district’s problems, even going so far as to portray it as a system on the upswing.

What follows is the story of my first year teaching in New Orleans at John McDonogh Senior High School, which I share as a rejoinder to all of those who claim the district was in good shape in the years before the storm, as well as a reminder of just how far our public schools have come.

Preparations

I

spent the summer of 2002 preoccupied with planning for my first year teaching at John McDonogh Senior High School. In retrospect, I expended an inordinate amount time trying to prepare for the challenge of classroom management. It was an obsession that stemmed, in part, from the fact that every teacher I turned to for advice said that my success or failure in that first year would hinge on my ability to control my class. Yet it was also because I knew John Mac had a reputation as one of the toughest schools in the city. Its notoriety was driven home by a woman in the district’s central office, who, after learning I was going to teach at John Mac, simply responded, “Well, I’ll be praying for you.”

And so, I spent many hours drafting and revising my rules and consequences, before revising them some more. I sought out seasoned high school teachers to squeeze all the wisdom I could out of them. I tried to envision and plan for every possible thing that could go wrong in that first month of school – i.e., the honeymoon period – when setting a good tone could mean the difference between nine months of sanity or hell.

Thus, I entered John Mac – and the New Orleans Public Schools system – with the assumption that the biggest challenges I would face would come from students: disrespect, fighting, truancy, and every other stereotype one associates with inner-city schools. And, I would be dishonest if I didn’t admit there were plenty of occasions when I was cussed up and down, when I had to break up a fight, or when I found myself on a student’s doorstep asking why they stopped coming to school. But in spite of these issues, I genuinely liked my students, and although they sometimes griped at the outrageous idea that I expected them to do work (yes, even on Friday afternoons before holidays), they genuinely liked and respected me in return. It was the students that made we want to come to work each day.

No, what I didn’t anticipate was that the greatest challenges I would face – as well as the most frustrating – came from adults. I mean adults at many levels: school leadership, district administrators and support staff, the school board, and to a certain extent, the broader community.

The School Year Begins

T

he near-total breakdown of the system was evident as soon as I walked through the door on what was supposed to be the first day of class. I say “supposed to be” because, to my surprise, the main office hadn’t gotten it together over the summer to assign students to classes. As a result, I spent the better part of that first week trying to keep a room full of freshmen occupied with busywork while administrators scrambled to put together rosters. Needless to say, I was better prepared when the same thing happened again the following semester.

Then there was the deplorable state of the building, which was decrepit in the most literal sense of the word. As a science teacher, I was assigned to what had been a lab classroom on the third floor, although it barely resembled such after years of neglect. Lab benches sat broken and unmoored from the floor. Ancient linoleum tiles cracked and scattered underfoot. Panes were missing from the windows. The monolithic heating and cooling unit rarely worked (no matter how many technicians from Johnson Controls interrupted class to tinker with it). There was even a hole in the floor – albeit, not much wider than a quarter – through which you could peer into the classroom below.

Initially, I assumed I was assigned the room because I was a rookie, the low man on the totem pole. However, after the first substantial rain, I was just thankful to have a classroom that didn’t have water pouring down from the ceiling. It was painfully clear the district had long before abdicated its responsibility to properly maintain the building. Repairs, when addressed, were largely improvised: holes in the walls were covered over with plywood; sheets of plexiglas were screwed onto mouldering window frames; errant lengths of electrical wire were tied up in bows that hung from the ceiling. Plus, nearly everything was coated in a dreary shade of pine green paint in a lame attempt to mask the wear-and-tear.

In terms of materials, things were no better. At the beginning of the year, each teacher at John Mac was given $25 for supplies, a stack of so-called Form 44s to record grades and attendance, and four reams of copy paper (the last being somewhat of an empty gesture, as the Xerox machine would breakdown for days and weeks at a time). My first semester, I had students sitting on unopened boxes of textbooks because there weren’t enough chairs. The following term, there were plenty of chairs to go around, but not enough textbooks. On top of this, I faced the considerable challenge of teaching chemistry without a working lab or equipment. As a result, I spent several evenings in those first weeks scouring branches of the New Orleans Public Library for children’s science books with simple experiments that could be conducted with items like Borax, ammonia, and baking soda.

I also spent hours rummaging through an old supply closet in my classroom that was packed to the hilt with discarded books, faded rolls of kraft paper, broken overhead projectors, and so forth. I was looking for anything salvageable I could use for class, but it felt like I was excavating an archeological site: each stack of junk I removed revealed another older than the last. Towards the back of the closet, I found a forgotten cache of chemicals dating back to the late-1950s, some of which had corroded through their containers and onto the floor. I grabbed a few intact jars, along with a dusty box of test tubes and beakers, and resolved to teach chemistry as best I could.

I didn’t enter John Mac with any romantic notions of what I was getting myself into – I expected things to be bad – but when I think back on that first month or so of school, I remember feeling overwhelmed nonetheless. Every day, there was a moment when I would think to myself: This place couldn’t be any more fucked up. But soon thereafter, as if on cue, something else absurdly pathetic would happen (like the time a mouse suddenly fell from the drop ceiling in the middle of class) to confirm things at John Mac were more fucked up than I ever thought possible. They were also terribly depressing. The disorganization, the disrepair, the lack of even basic supplies, it all sent a clear and undeniable message: the education of these students is not important.

A Brief History

J

ohn McDonogh occupies a full city block along Esplanade Avenue, a Spanish Oak-lined street that follows a ridge of high ground (or what passes for it in a city largely below sea level) that extends between the Mississippi River and Bayou St. John. It was the favorable elevation that drew Creole families, eager to escape the cramped and dingy confines of the Vieux Carré, in the middle of the 19th Century, when the city stood at the center of the world’s cotton trade. They built grand Greek Revival mansions along the boulevard and soon the surrounding neighborhood emerged as the hub of the city’s francophone elite. In fact, John McDonogh sits just a few doors down from the house where Edgar Degas composed A Cotton Office in New Orleans, the painting which first brought him widespread recognition as an artist.

By the time I arrived, the neighborhood – much like the city itself – had seen better days, though it retained a sort of shabby elegance. You could still drive down Esplanade and admire the old mansions, but a closer inspection revealed that the wealth that built them had long since departed. Similarly, John McDonogh’s imposing brick facade, wide hallways, and arched entryway hinted at a more prosperous period in the school system’s history, an era ushered in by the election of Mayor Martin Behrman in 1905.

Although now primarily remembered for shuttering Storyville, the city’s infamous redlight district, Behrman’s list of accomplishments during his four-and-a-quarter terms in office are unrivaled by any politician in the city’s history. He vastly improved and expanded the city’s sewerage and water system, created the Public Belt Railroad, paved the city’s streets, and helped bring an end to the scourge of Yellow Fever epidemics that had taken the lives of over 40,000 New Orleanians in the preceding 90 years.

If this wasn’t enough, Behrman also oversaw the most profound period of change the city’s public schools would know until Hurricane Katrina. Ever since its first public school opened its doors in 1841, the city’s education system suffered from inadequate funding, mismanagement, and low enrollment. The myriad challenges facing the public schools were aptly summed up by Superintendent William O. Rogers, whose 1884 annual report on the school system lamented: “Public education is an anvil on which a good many hammers have been worn out.”

By the turn of the century, when other major American cities had adopted compulsory education laws, less than a third of New Orleans children were enrolled in school, and only a fraction of those enrolled went on to earn a high school diploma. As the public’s frustration mounted over the inadequacies of its schools, civic organizations across the city began agitating for a broad overhaul of the system. Their calls for reform gained impetus in 1909, when the Russell Sage Foundation released Laggards In Our Schools, a damning report on the state of American public education which ranked New Orleans an embarrassing 59th out of 61 large urban school systems (just barely beating out Camden, New Jersey, and segregated black schools in Nashville).

Recognizing that improving public schools was good politics, Behrman proclaimed himself the “School Mayor of New Orleans,” and used his control over the local Democratic Party machine to pack the school board with loyal apparatchiks. In short order, he pushed forward a series of measures that quadrupled the city’s annual public school appropriations, raised the average teacher salary by 166%, and increased student attendance by over 40%. Behrman also launched a school construction plan so ambitious in scope that by the time of his death (in office, no less) in January 1926, one out of every three schools in the city had been built under his watch.

One of those schools was John McDonogh, which originally opened as Esplanade High School in 1912. It served as the downtown white girls’ high school until 1952, when the school went co-educational while retaining its racial exclusivity. In those decades, John McDonogh had a solid academic reputation, as well as a formidable record on the athletic field, and was generally considered one of the best high schools in the city – that is, for white families. African-Americans, on the other hand, were relegated to a second-class public education system that was separate from and most definitely not equal to that of whites. A 1940 report, Tomorrow’s Citizens, laid bare the stark inequities that existed between the city’s white and black public schools, noting that the latter suffered from “overcrowded classes, poor building facilities, inadequate staff and a shortage of teachers.”

Enlarge

Following the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board, the Orleans Parish School Board waged a long, but futile battle against integration. For four years, district officials ignored a federal court order to establish a desegregation plan. Finally, in March 1960, an exasperated Judge J. Skelly Wright issued his own plan that he intended to implement in the upcoming school year. In response, OPSB member Emile Wagner formally proposed that the board shutdown all of the city’s public schools and reopen them as state-financed private academies. That idea was ultimately rejected by parents in a survey circulated by the board, but OPSB continued its legal fight for several more months. Nevertheless, on November 14, 1960, four brave little girls enrolled at two formerly all-white elementary schools – William J. Frantz and McDonogh No. 19 – and the death knell of school segregation in New Orleans (or more accurately, de jure segregation) was sounded.

By the time John Mac finally integrated in 1967, any cautious hope that desegregation might help bridge the city’s racial divide had faded. As the historians Donald DeVore and Joseph Logsdon wrote:

“Desegregation placed a massive burden of responsibility on the school system. But rather than accept the challenge of reform, most New Orleanians abandoned the public schools.”

Beginning in 1970, white families began leaving the district en masse, with middle-class black families soon joining the exodus. By the end of the decade, white enrollment in NOPS had fallen by more than half, and by the late-1980s, the district’s student population was largely poor and overwhelmingly African-American.

With so many white and middle-class black children now attending private or parochial schools, their parents – the city’s political and economic backbone – no longer had a vested interest in the school system. Their disengagement allowed lesser lights and those with dubious motives to ascend to positions of leadership on the school board and within the district administration. As the years passed, the school system’s problems mounted and its downward trajectory accelerated. By the early 2000s, NOPS was the second-lowest performing district in the state and was plagued by governance problems, high turnover, and financial mismanagement.

My New Abnormal

A

ll I can say is thank god for Manuel 1. Manuel was a second-year TFA corps member who had somehow survived his first year at John Mac and therefore took it upon himself to “onboard” me, often over beers, in the weeks leading up to the start of school. During one such conversation, he matter-of-factly recounted a fight he witnessed in which two girls began slashing each other with razorblades. When he looked up and noticed the holy-shit-expression on my face, he quickly added, “But you don’t have to worry about fights for the first couple weeks because half the kids won’t show up until after Labor Day.”

While I never encountered any razorblades, approximately 30% of the district’s 70,000+ students were absent on the first day of the 2002-03 school year, a figure that edged closer to 40% at John McDonogh. For the first four weeks, I was welcoming new students to class practically every day; it wasn’t until well into September that my rosters finally stabilized. Although the constant influx of late arrivals caused major headaches, administrators did little to discourage the behavior and students weren’t marked absent for the days (and in some cases weeks) they missed.

But students weren’t the only ones with attendance problems. Article 16; Section 1, of the United Teachers of New Orleans’ collective bargaining agreement with the Orleans Parish School Board stated:

“All members of the Bargaining Unit who are initially hired for a school session shall be credited on the date of reporting for duty with ten (10) work days to be used for personal illness and/or emergency…All members of the Bargaining Unit, upon the completion of their first full or partial school session who continue their employment, shall be credited with an additional ten (10) work days to be used for personal illness and/or emergency.”

What this meant is that a full-time teacher in the district could to take up to 20 sick days over the course of an 180-day academic year without penalty, and unfortunately, many of them did. About 10% of the faculty at John Mac was absent on any given day, a percentage that tended to double before and after holidays and long weekends. With an insufficient number of substitutes to cover so many absences, students could easily find themselves sitting in classes totally unsupervised. As a result, many joined the sizable crowd of students who were constantly running the hallways, while others hid out in the gymnasium, where the adults rarely asked them why they weren’t in class.

That’s not to say that teachers alone were to blame for the problems at the school. Some of the most inspiring people I’ve ever met were teachers who worked at John Mac year after year because they wanted to serve the kids who needed them most. Others started out with the best intentions, but saw their energy and enthusiasm worn down by a system that, in many respects, worked against them. Then, unfortunately, there were those individuals who had no business being in a classroom, the teachers who sat behind their desks with a newspaper while their students lounged about or slept.

It wasn’t a big secret that there were teachers who weren’t doing their jobs. We all knew who they were, but no one ever held them accountable for it. In all the time I spent working with NOPS, I never knew anyone who lost their job due to incompetence or dereliction of duty. In reality, there only two circumstances under which you could get fired: you either hit a student or were accused of “inappropriate conduct.” Even these misdeeds didn’t result in immediate termination, as I learned soon after the school year started when a colleague made sexually-explicit remarks to several female students. For months afterward, he arrived at school each morning, signed in, and was paid to sit in the main office until dismissal.

Meanwhile, I spent the first three months of school trying to figure out what I should teach in my classes. The unit plans I spent untold hours to develop at the beginning of the year were so ambitious that they were basically worthless. My juniors and seniors were so far behind that we spent much of our time in class focused on remediation. I constantly debated whether to push forward with chemistry content, or simply focus on the skills they needed to pass the Graduation Exit Exam (GEE). When I surveyed my students, I was startled to find that many had already taken chemistry but failed. There were also several overage individuals on my rosters, including a young man who had just celebrated his 20th birthday – a fact no one noticed when he showed up to enroll.

But the biggest shock came from the realization that many of my students were, for all intents and purposes, functionally illiterate. Then, as now, many insisted that poverty was to blame for the academic shortcomings of kids like mine at John McDonogh. Yet poverty alone could not explain away why, after more than a decade of school, so many of them still struggled to sound out elementary words. Listening to my students stammer through basic sentences brought to mind the same infuriating questions: How are they ever going to pass the tests they need to graduate? How did they get to high school without knowing how to read? Why were they simply passed along year after year?

Tutoring At Wicker

A

fter months of dealing with teenagers and problems they brought with them to class, I began to wonder whether I should have taught elementary school. To be honest, working at John Mac often felt more like triage than teaching. So when Rachel, a fellow TFA corps member, asked if I would be interested in tutoring her third graders after school at Albert Wicker Elementary, I jumped at the opportunity.

Wedged between the Iberville and Lafitte housing projects, Wicker was less than a mile from John Mac and was the elementary school that many of my students attended. A few afternoons a week, I headed over there after class, arriving early enough to observe the last half-hour before dismissal. It was an experience that always dispelled any regrets I had about teaching high school. Little people ran around me in the hallway in every direction: crying children, fighting children, laughing children, yelling children. Teachers barked at students as their classrooms slid into chaos.

Although one of the district’s newer school buildings, Wicker was a victim of the “open-space school” movement of the early-1970s that rejected traditional classrooms in exchange for large common learning areas. It was a terrible idea. Teachers compensated by demarcating the boundaries of their homerooms with bookshelves and rolling bulletin boards, but it did little to block the noise (nor the occasional fusillade of spitballs) coming from neighboring classrooms. During dismissal, the open layout of the building only amplified the cacophony, and I often found myself walking toward Rachel’s class with a renewed appreciation for the simpler things in life, such as doors and interior walls.

Yet when I arrived, I was always amazed by Rachel’s ability to keep her homeroom calm and orderly while the rest of the school rapidly approached meltdown. For one thing, Rachel was a petite, blonde-haired, blue-eyed, Jewish girl from Boston, which in the context of Wicker meant she might as well have been from Mars. Her students initially took advantage of that fact and for the first few months she struggled, particularly with discipline. But Rachel regrouped, borrowed some tried-and-true classroom management techniques from veteran teachers and thereafter ran an exceedingly tight ship. She also built strong relationships with parents, who were soon on the lookout for the daily behavior reports she sent home with each child. During my first few visits, more than one student felt compelled to quietly warn me, “That lady don’t play, Mr. Cook.”

But Rachel also made learning fun for her students. Many of my afternoons at Wicker were spent helping with any number of projects she planned for her kids. We wrote stories, held multiplication tables competitions, and made puppets out of tube socks. I even volunteered to chaperone when Rachel took her class on field trips canoeing in the wetlands around New Orleans. I enjoyed spending time with the cast of characters in her class: they were cute, funny, and still possessed a sense of optimism about the world that many of my own students had lost.

On the other hand, the more time I spent at Wicker, the more my high schoolers’ academic deficits began to make sense. Much like John Mac, the quality of teaching at Wicker ranged from excellent to downright awful and the dichotomy was beginning to catch up with the school. In the spring of 2002, 17.8% of 4th graders at Wicker scored Basic or above on the English/Language Arts portion of the state’s high-stakes LEAP test; in math, it was only 12.5%. The high failure rate meant dozens of students were retained. The results were so bad that when testing rolled around again the following year, the principal invited a local pastor to offer a prayer over the P.A. system seeking divine intervention.

Furthermore, the stories Rachel told me about the goings-on at Wicker were, in some ways, more outrageous than anything I encountered at John Mac. One Friday afternoon, Rachel watched in disbelief as her principal loaded food from the cafeteria – food that was, obviously, intended for students – into her car before driving away for the weekend. Then there was the time a teacher dispensed with testing protocol to deep fry tilapia on a fire escape while her students dutifully took the LEAP. More serious was the panic that broke out when a second grader was discovered at school with a loaded handgun – an incident that the principal managed to keep covered-up and out of the newspaper.

A Culture of Corruption & Denial

I

wasn’t surprised that Wicker’s principal was able to keep the gun situation under wraps. Although there seemed to be a new NOPS scandal in the pages of the Times-Picayune each week, reporters never uncovered more than a fraction of the shenanigans going on in the district. Their job was made difficult thanks to a code of silence that seemed to pervade every level of the organization.

Whenever a potentially embarrassing incident at school occurred, the message from those in charge was shut your mouth. After all, if you brought attention to a problem, folks might start poking around and god only knew what they might find. It was better for everyone, as our principal once told us in a faculty meeting, to “keep it in the family, we’ll deal with it.”

Of course, the problems were rarely dealt with; they just grew and multiplied while everyone tried to go on about their business in spite of them. In fact, if the district excelled at anything, it was pretending as if everything was normal, but the advent of statewide standardized testing made the crisis in New Orleans schools impossible to ignore.

In 2003, Times-Picayune education reporter, Aesha Rasheed, brought that crisis into sharp relief with the heartwrenching story of Fortier High School senior Bridget Green. Green had been named valedictorian of her graduating class based on her stellar G.P.A., but the honor was later rescinded after she failed the mathematics portion of the GEE. Green wasn’t allowed to participate in commencement exercises and only passed the test – by one point – months later on her seventh attempt.

“The New Orleans public schools failed Bridget Green,” proclaimed a Times-Picayune editorial. “And if they failed her…then one has to conclude that they failed most of the students who earned lower grades than she did.”

As the depth of NOPS’ academic problems were becoming clear, all pretense of responsible district governance collapsed. Between 1998 and 2005, the school system cycled through eight superintendents. Monthly meetings of the Orleans Parish School Board regularly devolved into a circus, with the activist Sandra “18-Wheeler” Hester serving as ringmaster. Financial improprieties led to FBI investigations, indictments, and a school system debt that ballooned to $265 million by the summer of 2005.

To top it all off, a series of high-profile corruption scandals wracked the district in the years leading up to Katrina, each one more brazen and outrageous than the last:

- In 1998, an exposé in the Times-Picayune revealed that at least $3.4 million in OPSB property had been stolen in the previous five years, primarily by school district employees. At the time, the district’s chief investigator complained that school records were “in such disarray that weeks must be spent determining first if there has actually been a theft or the property is somewhere in the building.” Superintendent Morris Holmes announced his resignation soon after the scandal broke.

- In 2001, another in-depth investigation by the Times-Picayune revealed that 77 out of 79 schools saw suspicious jumps in their standardized test scores over the previous five years. An editorial on the scandal noted, “In several dozen cases, a group of children saw their scores swing by at least 50 points from one test to the next, which the testing experts say is impossible without cheating.”

- The following year, another superintendent, this time Alphonse Davis, was pressured to resign after it was discovered that his father, a janitor at Carver High School, had earned $38,754 in overtime over and above his base salary of $27,738. Investigators claimed the elder Davis would have had to work 35 hours of overtime a week, every week of the year to amass such an amount.

- In June 2003, an auditor’s report found that NOPS misspent approximately $20 million in the previous three years, much of it the result of payroll fraud. The investigation showed the school system provided checks to nearly 4,000 people who didn’t deserve them, including individuals who were retired, fired, and in a few cases, even dead. Then-OPSB member Jimmy Fahrenholtz told the Los Angeles Times, “When checks are regularly sent to dead people, and they’re cashed, you know you have a major problem.” After the report made headlines, more than 300 individuals suddenly stopped picking up their paychecks from the central office.

- In 2004, a Federal grand jury indicted 11 NOPS employees on corruption charges including extortion, insurance and mail fraud, and check forgery. A press release from U.S. Department of Education’s Office of the Inspector General stated at the time: “This latest set of indictments of eleven defendants brings the total number of persons charged to date with fraudulent activities involving the Orleans Parish School Board to twenty-four.”

Corruption at the highest levels would even impact me directly. In the fall of my second year, construction workers showed up unannounced in the middle of the school day to take over my classroom and install an “I CAN Learn” computer lab. For the rest of the semester, I was relegated to the auditorium, where I unsuccessfully attempted to cordon off a quiet corner to hold class. Five years later, Orleans Parish School Board President Ellenese Brooks-Simms pled guilty to taking $140,000 in bribes connected to the “I CAN Learn” contract and was sentenced to 18 months in Federal prison.

Spiraling Out Of Control

F

or five consecutive years, between 2000 and 2004, New Orleans was the murder capital of the United States. The killing peaked shortly after I arrived in 2003, when the city recorded nearly 60 homicides for every 100,000 residents – a rate eight times the national average. Of New Orleans’ 275 murders that year, half occurred within the so-called “The Hot Zone,” a seven-square-mile area that included both Wicker and John Mac.

Nearly all of the victims were poor, black, and marginalized by society. They were the product of a system that had tossed them aside, a system that included the public schools, which had left them under-educated and with few marketable skills. It wasn’t hard to understand why so many young people found themselves involved with one of the city’s gangs. The drug trade, with its promise of cash, a fancy car, and respect (or more often fearful deference) was hard to resist.

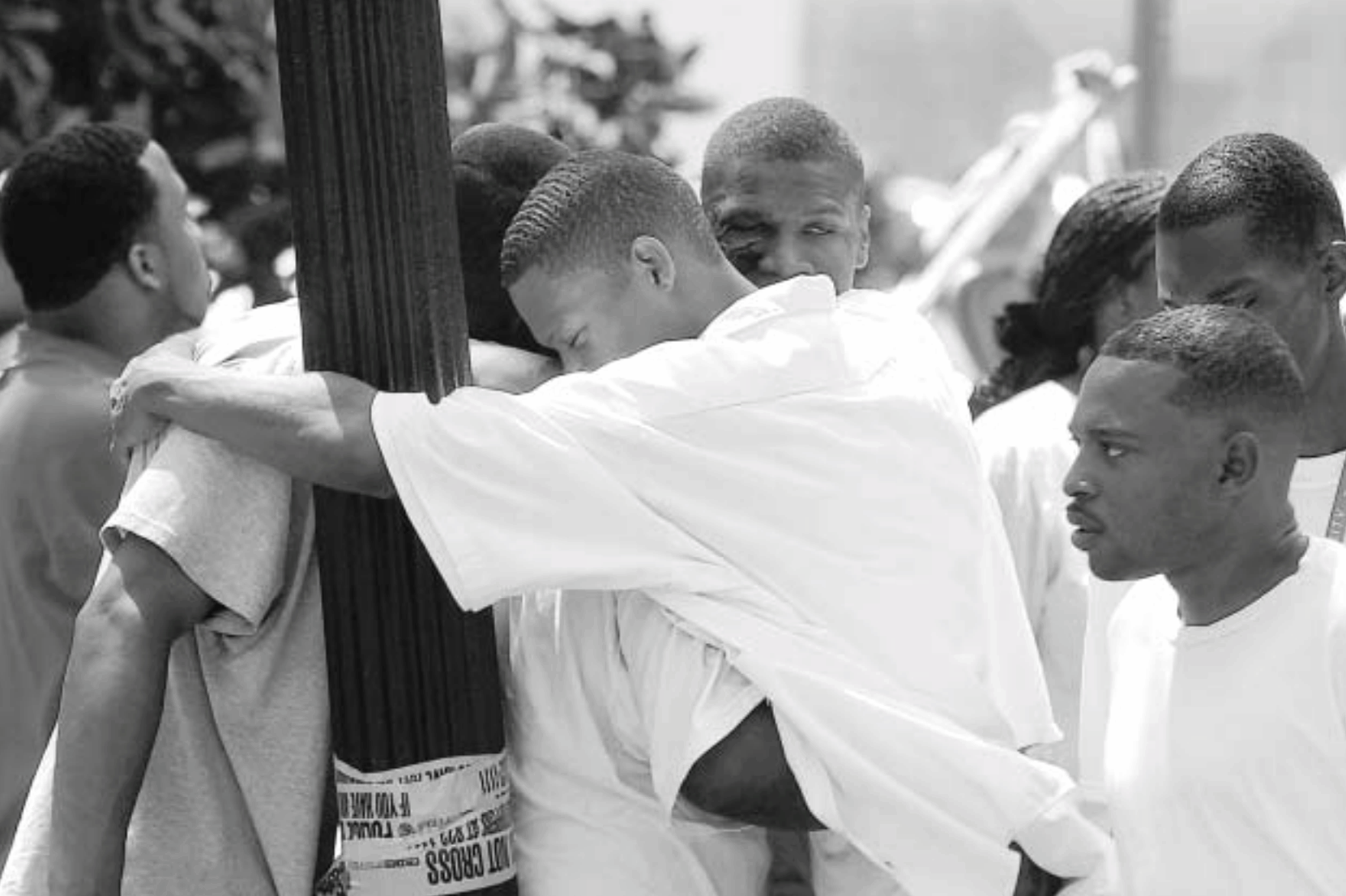

Enlarge

As the school year dragged on, there was a palpable sense that the mayhem out on the streets was working its way into the corridors of John McDonogh. I began to notice the increasing regularity of daily announcements that noted the passing of a former John Mac student whose life had met a violent end. More and more students started showing up at school sporting various gang colors. Then, one memorable afternoon, a guard suddenly burst into my room and dragged a student from her desk and out the door. When I went to the main office to find out why she was pulled from class, my principal showed me a 9mm Glock they retrieved from her bookbag.

Although officially a neighborhood-zoned school, John Mac enrolled students from across the city – and by extension, across various gang territories – bringing rival crews into close proximity. There was the C.T.C., from “Cross Tha Canal” in the Lower Ninth Ward, the 7th Ward Hard Heads who hailed from the St. Bernard Projects, and 3-N-G from the neighborhood surrounding the corner of Third & Galvez in Central City, among others. Their tags soon began appearing on walls, in the stairwells, and on desks throughout the school – a barometer of the rising tensions.

Thus, I was always on point, always trying to keep abreast of the latest beef between this gang or that, always seeking to preempt or defuse conflicts. Still, fights broke out all the time, especially during transitions, when scores of students clogged the hallways. In between classes I would stand in my doorway watching for any hint of trouble: two students sizing each other up, a burst of shit-talking, the exaggerated swaggering that precedes a brawl. And, when it erupted, my colleagues and I would jump in to try and break it up.

One day, as I walked toward the faculty lounge, a huge fight broke out in front of the auditorium. As suddenly as a clap of thunder, twenty students were in a scrum, all punching, kicking, and tearing at each other’s clothes while onlookers crowded around to watch. I joined two or three other teachers to pull the two sides apart, but the ferocity did not abate. It only ended when an NOPD School Resource Officer ran up and doused the throng with pepper spray – teachers included – sending us reeling in every direction, watery-eyed and wheezing from the burning aerosol.

Pepper spray notwithstanding, we were lucky the NOPD officer showed up before someone got seriously hurt. John Mac had a contingent of OPSB security guards who were armed and clad in all-green uniforms, but they couldn’t be depended on to keep the peace. Whenever you called for security you were rolling the dice: sometimes they arrived immediately, while other times they didn’t show up at all. If anyone ever complained, guards were quick to remind everyone within earshot that they only took orders from the central office.

The kids knew better than anyone that security at the school was a joke. Every student who walked through the door in the morning was subject to screening, but guards only briefly glanced into their backpacks before sending them through a metal detector that wasn’t even plugged in. Moreover, tardiness was a chronic problem, with students trickling into school throughout the day, long after the guards had left their post at the main entrance. That meant a constant flow of people were entering and exiting the building unannounced and unnoticed.

As the problems escalated, teachers began fearing for their own safety. I joined a group of faculty members who began to hold informal meetings after school to discuss how to stem the growing anarchy in the building. We circulated a petition urging our principal to enforce various rules, including the requirement that students wear their school IDs, but our demands were never taken seriously. Likewise, complaints we made to UTNO representatives about the school’s growing safety concerns were ignored. As a result, many teachers resigned themselves to the fact that nothing was going to be done. They simply locked their classroom doors, crossed their fingers, and waited for the school year to end.

Monday, April 14th, 2003. 10:20am

A

pril is probably the best month of the year in New Orleans. The days are clear and warm, but without the oppressive humidity that soon covers the city like a blanket. It also marks the beginning of festival season in South Louisiana, when communities emerge from the sober repentance of Lent to once again embrace the joie de vivre that characterizes the region’s culture.

I must admit, it was rubbing off on me. I was in a pretty good mood when I arrived at school on the morning of that second Monday in April. It was beautiful outside and I had just spent the weekend at my first French Quarter Fest. I was finally beginning to feel like I was getting a handle on the whole teaching thing. Plus, the chaos at school had even begun to subside, no doubt due to the sharp drop in attendance that occurred after GEE testing in March.

First block was my free period, so I grabbed a cup of coffee, opened the windows in the back of my room to let in the breeze, and spent the morning lazily preparing for class. When the bell rang and my sophomores filed into the room, I was all smiles and jokes as I greeted them. After they settled into their seats, they got started on their warm-up as I walked around class to answer questions.

Suddenly, the silence was interrupted by a large, hollow bang from behind the building. For a split second, I thought a trash truck was emptying the dumpster.

Then all hell broke loose.

A barrage of gunfire rang out, followed by a sickening chorus of screams. I ran to the windows at the back of the room, my students following close behind, to witness a horrible scene unfold in what seemed like slow-motion…

Hundreds of terrified students surged out of every exit of the gym, trampling those who fell in the onrush…

Some cowered behind any barrier they could find, while others jumped the fence and ran as fast as their feet could carry them…

Children were crying, vomiting from fear and digust, and frantically looking in every direction for someone to protect them…

A fellow teacher tumbled out of a side entrance, screaming at the top of her lungs, “Oh Jesus Lord, HELP US! HELP US! HELP US!”

The one person who kept his head amidst the pandemonium was an unassuming 15 year-old special education student named Joshua Myers. I watched transfixed as Joshua calmly walked out of the gym carrying a wounded girl in his arms – shot through both of her legs – and gently laid her down as blood spurted on the pavement around her. Meanwhile, the school’s security guards appeared with guns drawn, yelling into their walkie-talkies and scanning the crowd, disoriented and unsure what to do.

I was snapped back to reality by a hysterical voice on the P.A. system screaming that gunmen were in the building and pleading for teachers to lock their doors. I ran over and double-checked it before herding my students into the farthest corner of the room.

Police cars soon began arriving from every direction, sirens blaring. Officers jumped out, weapons at the ready, and stormed into buildings to secure the campus and assess the situation. However, it was clear that many of my students already knew what had happened.

“They got Caveman,” one whispered to himself.

Jonathan “Caveman” Williams, age 15, was dead. Three others, including a student of mine from the previous semester, were wounded in the crossfire. Brian Thevenot, Michael Perlstein, and Tara Young later described what transpired in the gym in the pages of the Times-Picayune:

“At least two gunmen entered a gym door just 20 feet from Williams, rushing past two coaches before the school officials realized that something was amiss. One of the gunmen was armed with an SKS semiautomatic assault rifle — the Chinese-made version of the AK-47 — and the other with a 9 mm pistol. Williams reportedly was sitting in the bleachers when the pair opened fire, sending him sprawling to the floor, badly wounded. As chaos erupted throughout the crowded gym, the teen with the assault rifle stood over Williams, firing bullets into his body. They gouged the ceramic floor tiles, stirring up a dusty residue that soon would cover Williams’ face in an eerie gray-white mask, one investigator said.”

A forensic pathologist who later testified at the trial of the perpetrators told the jury that Jonathan was hit ten times before the shooting was over, including a shot fired at close range that “entered Jonathan’s right eye and exited through the top of his head.”

The attack was retaliation for his role in the murder of another teen, 18 year-old Hillard Smith, just a week earlier. Jonathan apparently knew he was a marked man: investigators found a .45-calibre handgun on his body that he had snuck past security earlier that morning.

Ambulances and TV news vans soon began arriving on the scene, along with hundreds of distraught parents looking for their children. As paramedics tended to the wounded, police began a thorough search of the building. When the office announced they would be calling down students as their parents lined up to retrieve them, it was clear we were going to be stuck in the classroom for a while.

Slowly, the weight of what had just transpired began to sink in and I sat with my students to listen as they talked about their lives. They spoke about friends and family members who had been killed, as well as their own close encounters with violence. They spoke about their efforts to steer clear of the gangs that wrought havoc on the streets. They spoke of the insanity of it all. But of all the things I learned about my students that afternoon, the saddest was that many of them felt a sense of inevitability that one day, they too would be cut down in a hail of gunfire.

Here were my kids, who I cared about, who struggled each day to come to school – who struggled just to survive in some cases – and what did we offer them in return? A subpar education in a shithole building where we couldn’t even keep them safe.

It made me angry. I was angry at the teachers who didn’t give a damn; at the administrators who ran their schools into the ground; at the board members who claimed they represented the community while stealing from its children; at the union reps who chastised you if you did anything more than the contract required; at the vendors who ripped off the district because they knew they could get away with it; at the rich Uptowners who watched with semi-amused detachment as the system consumed itself; at the activists who loudly beat their chests over the public schools while doing little to actually fix them. It was all a big farce and it was the children – tens of thousands of them across New Orleans – who paid the price for our sins.

One by one, my students were dismissed that afternoon, until I eventually found myself sitting alone in my classroom. Before I finally left the building that day, I captured a glimpse of what I now recognized was, in a sense, a consequence of the district’s failure. A bodybag was wheeled out of the gym and across the yard toward an awaiting New Orleans Coroner’s van. Two men unceremoniously lifted the gurney into the back, secured it, and slammed the doors shut, before joining a group of detectives for a cigarette.

As I turned to packup my things and head home, I noticed a bumpersticker on the Coroner’s van that asked a haunting question:

Have you hugged a child today?

—

- The names of my personal acquaintances in this story have been changed out of respect for their privacy. ↩

@petercook “Going Backwards” sobering look at being a tchr in NO in 2003 peterccook.com/2015/08/18/goi…

tag:twitter.com,2013:841754874043891713_favorited_by_422858867

Cade Brumley

https://twitter.com/petercook/status/841754874043891713#favorited-by-422858867

This is good news for the families of @BricolageNOLA

twitter.com/petercook/stat…

This is good news for the families of @BricolageNOLA

twitter.com/petercook/stat…

John Mac’s gymnasium, site of 2003 tragedy (pcook.me/36Sx), to be torn down, replaced: pcook.me/zNgW #NOLAed #LaEd https

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

RT @petercook: @kitty_ricketts Read this and then make that argument: pcook.me/16enn @vailjuju

RT @petercook: What were #NOLAed public schools like before #Katrina? Worse than you think: pcook.me/13lOl #edreform #longreads

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

RT @petercook: Had to share this note from a fmr #NOLAed student who read the story of my 1st year teaching: pcook.me/1ho2T

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

RT @petercook: Had to share this note from a fmr #NOLAed student who read the story of my 1st year teaching: pcook.me/1ho2T

RT @petercook: Had to share this note from a fmr #NOLAed student who read the story of my 1st year teaching: pcook.me/1ho2T

RT @petercook: Had to share this note from a fmr #NOLAed student who read the story of my 1st year teaching: pcook.me/1ho2T

likes this.

likes this.

As a former student of a N.O public school my initial thoughts before Reading this was…. “He is about criticize, belittle and slander the students and not talk about the real criminals” But this Gave me chills…. (Especially the part about Caveman) Finally someone who actually cares enough to tell the truth about the corruption and harsh school conditions we were forced to learn in. Thanks definitely will share this.

This was great. It really rang true.

Great piece. That incident was the crescendo to the disfunction in that school. Very well written. Some of the details I had forgotten, but this is just the surface. The interactions with the police, neighborhood response are just a few of the other things that contributed to the situation. I think you hit them all. Glad you are still making an effort.

Finally had a chance to read this. You are a beautiful man, Peter Cook. Very well written–and powerful subject matter. Thanks for taking the time to educate us.

Wowsa. Thanks for sharing this, Pete.

RT @petercook: 13 yrs later, I wrote down the story of my 1st yr teaching in #NOLAed schools: pcook.me/13QU5 #edreform

Pete, thank you for this truth.

Thanks Julie – and thanks for all you’ve done/do to “change the narrative,” so to speak! 🙂

Thanks for writing this, Pete. With all the 10th year anniversary remembrances, I find myself thinking back 20 years to when I first moved to NOLA. This is just exactly the tone and tenor of my experiences. Thanks for bringing me back.

likes this.

RT @petercook: 13 yrs later, I wrote down the story of my 1st yr teaching in #NOLAed schools: pcook.me/13QU5 #edreform

RT @petercook: 13 yrs later, I wrote down the story of my 1st yr teaching in #NOLAed schools: pcook.me/13QU5 #edreform

Thank you Amy so much!

Thanks so much Allison – I hope you’re well!

Thanks Jamie!

This Article was mentioned on brid-gy.appspot.com

Thanks Caroline!

RT @petercook: 13 yrs later, I wrote down the story of my 1st yr teaching in #NOLAed schools: pcook.me/13QU5 #edreform

I don’t know what to say other than you got it exactly right; it’s a sharp blend of personal experience and broader perspective that will, dare I say, educate. I hope this post travels far and wide. Awesome work.

likes this.

RT @petercook: What were public schools like back before #Katrina? This was my experience: pcook.me/16jcu #NOLAed #edreform

This is a fascinating piece. Thank you for sharing. Sadly, this story can be told from many of our schools in the inner cities. Something has to give. The people of New Orleans are lucky to have you. Keep fighting the good fight, Peter.

Thanks Larisa!

I’m looking forward to reading & sharing!

Thanks Dina!

RT @petercook: What were public schools like back before #Katrina? This was my experience: pcook.me/16jcu #NOLAed #edreform

Amazing work Pete.

This is so beautiful- thank you for working so hard on behalf of all those kids!

RT @petercook: What were public schools like back before #Katrina? This was my experience: pcook.me/16jcu #NOLAed #edreform

Thank you for writing this; something important to remember. Well done.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

RT @petercook: This is my story – Going Backwards: A Year in the Old New Orleans Public Schools… #NOLAed #edreform peterccook.com/2015/08/18/goi…

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

likes this.

Thanks John! 🙂

Awesome post Pete!!!!!

Thanks, Kelly!

I’m sorry! I was busy saving the world…Just kidding. Thanks for your kind words! :^)

Thank you, Kristin!

I’m flabbergasted, really, that you not only survived this but thrived in this…and that you felt compelled to fight the good fight even when it seemed impossible. Many thanks, my friend, for being the brave, intelligent and kind soul we always knew you were…even when we were too young to really understand and appreciate such character traits!

Excellent.

Read it, people! Better than anything you’ll find in the New Yorker this month.

Thank you for writing this. As the new Drew building was being dedicated today, I was thinking about how incredibly

hard that first year was and how thankful I was for people like you who talked me through it (or sat at your desk and checked email while I sat there and cried, depending on the day).

That was great Pete!