Although I like Jennifer “Edushyster” Berkshire personally, it’s safe to say that when it comes to education policy, we agree to disagree on most points. However, I think I finally found an education issue on which we are more-or-less aligned: independent charter school authorizers.

On Tuesday, Salon published an interview Berkshire conducted with the authors of a recent study looking at the perils and pitfalls that can occur when states have multiple independent charter school authorizers. These authorizers are usually universities or other large non-profit organizations that can grant charters to applicants and are often responsible for providing oversight for those charter schools.

To be clear, I disagree with a number of the points made in the interview.1 I also think that comparing independent charter authorizing policies to the subprime mortgage crisis is ridiculous, as well as grossly misleading. That being said, I have to admit I’m inclined to agree with the overall message: independent charter school authorizers are generally a bad idea.

Here’s why I think independent authorizers are bad policy and bad for the charter school movement…

I. More Authorizers = Less Accountability

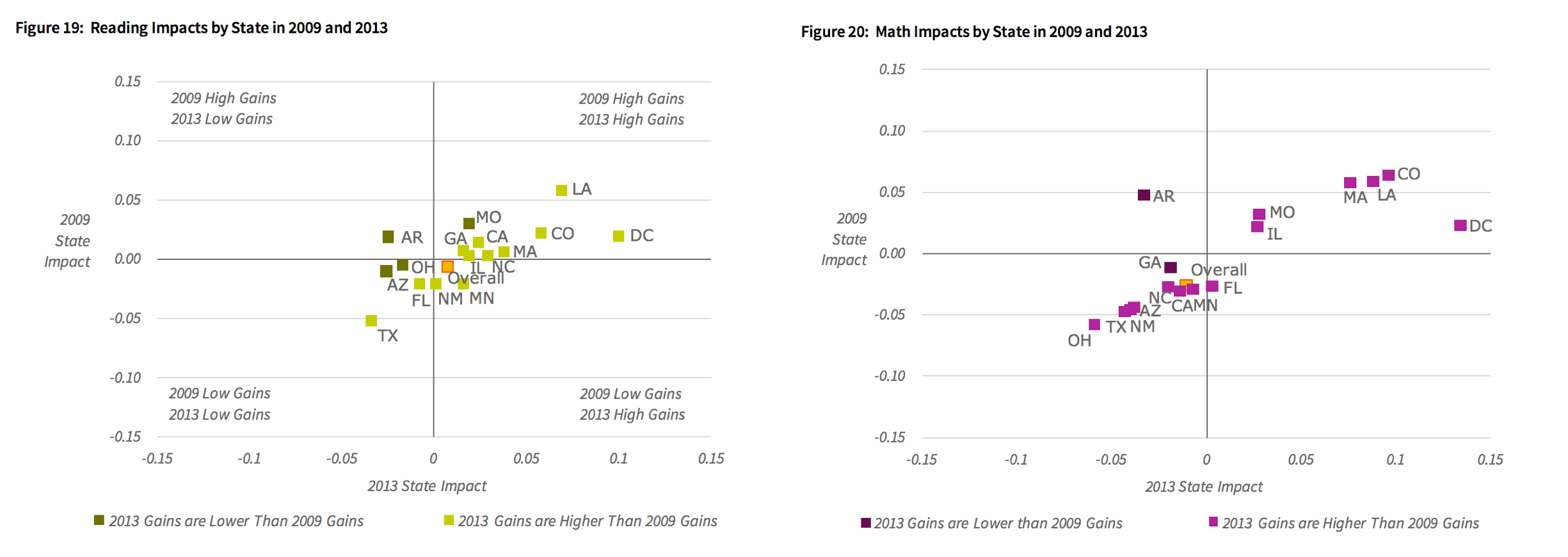

One of the most common arguments voiced by charter school critics is that charter schools as a whole have not produced better academic results than traditional public schools. Of course, this critique vastly oversimplifies the situation by ignoring the wide variation in charter school performance across the country. In some states, like Louisiana, charters outperform traditional public schools, while in other states the opposite is true.

Why do charters succeed in some states, but struggle in others? The evidence seems to indicate that charter authorizing policies play a big role. States with multiple independent authorizers, such as Ohio, tend to have lower performing charter schools. Matt Barnum over at The Seventy Four has written extensively about the Buckeye State’s troubled charter sector. In a recent review of Ohio’s push to reform their charter policies, he explained:

“The Ohio reform law is built on the idea that charter sponsors [i.e., authorizers] — organizations such as school districts, nonprofits, and universities — are in the best position to oversee schools’ performance. A frequent criticism of Ohio charters is that the sponsorship sphere is a free-for-all with so many players that poor-performing charters could shop for a new sponsor if they were threatened with closure and that sponsors themselves had little incentive to cut off bad schools.”

We see the same problem in Michigan, where state law allows community colleges and public universities to serve as authorizers. According to an article last month from the Associated Press, the effort to turnaround Detroit’s perennially failing education system has stumbled:

“Only five of 229 public schools serving predominantly Detroit students — traditional schools, charters and schools run by a state turnaround district — exceed the state average in reading. And just 4 to 7 percent of fourth- and eighth-graders are proficient in math and reading in the 2015 National Assessment of Educational Progress, dead last among 21 participating urban districts.”

These dismal results are due, at least in part, to the lousy oversight provided by independent authorizers. Over the past few years, droves of Detroit students have left district schools to enroll in charters overseen by 14 different authorizers and apparently many them have failed to ensure that their schools are raising student achievement. Michigan Governor Rick Snyder now wants to place the city’s charter and traditional schools under the oversight and control of a single board of commissioners with the power to close or reconstitute those that are failing. As Snyder told the AP, “There shouldn’t be a difference in how we treat a charter school from a public school in terms of transparency, openness and performance.”

Ohio and Michigan’s challenges illustrate what happens when there are too many cooks in the kitchen. The more authorizers you have, the harder it is to ensure they’re rigorously vetting charter applicants and holding them accountable for results.

II. Process Matters and Drives Perceptions

Last month, Louisiana’s Board of Elementary and Secondary Education (BESE) was supposed to decide whether to certify Southern University and New Schools for Baton Rouge (NSBR), an education advocacy non-profit, as the state’s first independent charter authorizers. However, State Superintendent John White pulled the item from BESE’s December agenda and it’s unclear if or when the board will take up the matter.

John White sends letter to BESE asking for delay in controversial charter school authorizations by Southern and New Schools BR. #LaEd

— Will Sentell (@WillSentell) November 29, 2015

Up to now, the authority to grant charters has been limited to local school boards and BESE – and many of the districts that would be impacted by the new authorizers want it to stay that way. They worry that independent authorizers would approve charters in their districts without consultation and without accountability to the district’s stakeholders. More importantly, district officials are concerned that an influx of charter schools would siphon off funding.

That last concern is often offered as a rationale when school boards deny charter applications. And, although charter school supporters are sometimes loathe to admit it, it’s true: every student who leaves a traditional district public school for a charter takes at least some of their per-pupil funding with them. That doesn’t mean that school boards should stifle charter school growth in their districts, but it does mean there needs to be a deliberative process where the competing demands of charter operators, districts, and stakeholders can be considered.

State and local school boards (or in some places, like Mississippi, state charter school authorizing boards) are the most appropriate arenas for that process to take place. That’s why we have them. Because independent authorizers make their decisions outside the established political process, they only lend credence to reform opponents who characterize the charter movement as “privatization”. Moreover, if a state has the right policies in place, such as appeals for rejected charter applicants, it’s hard to make a strong case for the benefits of independent authorizers – unless the argument is that they allow charter applicants to sidestep the political process.

- For example, at one point in the interview, co-author Preston Green says, “In New Orleans, for example, charters have been sued for failing to provide students with disabilities with an education.” Actually, both the Recovery School District and Orleans Parish School Board – which means both charter and traditional schools – were sued over special education concerns. That lawsuit was settled last year. ↩

@morganripski Oh and how hospitable are districts when outside authorizers approve schools in their districts that they oppose?

@morganripski Given the choice between successful charters and everyone feeling warm & fuzzy, I’ll choose successful charters, thank you.

@petercook riiiight. I hear districts are super hospitable to charters who’ve been approved on appeal

@morganripski Perhaps you didn’t make it this far:

@petercook you’re saying local boards have no financial interests? Last I checked, they fund schools too.

So, increase accountability by allowing boards who’ve operated failing schools for years to authorize #charters? Really, @petercook?

@petercook @rrm402 A: Too much school “choice”?

Peter – What is your theory on why JW pulled the Authorizer recommendations and why it doesn’t appear on the agenda next week?

I’m told NSBR may have had second thoughts about being an authorizer. At this point in the game, even if they were certified as an authorizer, any schools they approved couldn’t open until the 2017-18 school year. I have no idea what the deal is with Southern, although I thought it was interesting that the resolution being passed around by LSBA only referenced NSBR and not Southern for some reason.