Last week, The Intercept published an article by Aída Chávez and Rachel Cohen claiming that education officials in Puerto Rico are planning to take over the territory’s traditional public schools and convert them to charters.

To put it bluntly, it’s a great work of fiction, but a terrible piece of journalism – one that’s piled high with inaccuracies and unsubstantiated claims. It also lacks any pretense of journalistic objectivity, presenting charter schools and the reformers behind them as boogeymen intent on destroying public education.

Although Chávez is a relative newcomer to the education reform war, for those who are familiar with Cohen’s previous work at the American Prospect, the anti-reform bias of this piece should come as no surprise. That being said, the issues in Chávez and Cohen’s recent article are particularly egregious and I’ve therefore decided to pick apart the six biggest problems below.

1. There is no evidence that officials are plotting to “privatize” Puerto Rico’s public schools.

Chávez and Cohen open their piece with a vignette about the struggle to reopen Escuela Adrienne Serrano, a small school on Vieques, in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria. Although teachers and administrators almost immediately went to work to get the school up-and-running again, education officials told them they could not reopen until the building was inspected to ensure it was safe. The staff ignored the directive and began welcoming back kids until recently, when they ran out of potable water. Now, they have to turn students away.

On its face, it’s a small glimpse of the painstakingly slow pace of Puerto Rico’s recovery, but Chávez and Cohen assert the school’s plight is a consequence of something far more sinister:

“The guerrilla campaign to open schools is running headlong into a separate effort from the top, to use the storm to accomplish the long-standing goal of privatizing Puerto Rico’s public schools, using New Orleans post-Katrina as a model.”

That’s a pretty bold statement. Most journalists would want to provide evidence and additional context to substantiate such a claim. For example, who exactly has had the long-standing goal of privatizing the commonwealth’s public schools? What steps have those nameless figures taken in the past to advance it? How are they taking advantage of the disaster now to takeover schools? We’re never told the answers to any of these questions.

Instead, Chávez and Cohen cite an October news article (rough English translation here) in which the director of Puerto Rico’s Public-Private Partnership Authority “spoke optimistically about leveraging federal money with companies interested in privatizing public infrastructure.” However, if you actually read the article they link, you won’t find any mention of schools or the education system because the director was referring to a plan to outsource concessions and toll collection at Luis Muñoz Marín International Airport in San Juan.

How does that constitute proof of a plot to privatize public schools? I’m not sure either.

2. They distort statements made by P.R. Secretary of Education Julia Keleher (and Keleher herself).

Chávez and Cohen also insinuate that Puerto Rico’s Secretary of Education, Julia Keleher, intends to pursue New Orleans-style reforms by distorting her recent statements on social media, including the following tweet:

Sharing info on Katrina as a point of reference; we should not underestimate the damage or the opportunity to create new, better schools pic.twitter.com/Fmq59W4pKF

— Julia Keleher (@SecEducacionPR) October 27, 2017

To the authors, this is proof that Keleher has “already called New Orleans’s school reform efforts a ‘point of reference.’ ” But was she referring to NOLA school reforms or the challenge of rebuilding schools destroyed in a disaster? The fact that her tweet includes photos of construction sites and a newly built school suggest it’s the latter.

Before turning to other matters, the authors add that Keleher ran a management consulting firm prior to her appointment as Secretary of Education, while curiously omitting more relevant biographic details, like the six years she spent at the U.S. Department of Education or the seven she served as a district administrator. Are they trying to suggest to readers that she comes from the business world and therefore must be a “corporate privatizer” hellbent on dismantling Puerto Rico’s public schools? Me thinks so.

3. No, Jeanne Allen wasn’t involved in New Orleans’ school reform efforts.

Next, Chávez and Cohen turn to Jeanne Allen, CEO of the Center for Education Reform, who true to form, tells them exactly what they want to hear. Allen says she believes reformers “should be thinking about how to recreate the public education system in Puerto Rico,” and hopes that both brick-and-mortar and virtual charters will turn their attention to the island.

Of course, Allen is entitled to her opinions, but that doesn’t mean anyone is listening to them. In fact, she admits that folks in the reform community haven’t been talking about Puerto Rico at all, which undermines the contention that they’re working from the top down to seize control of the public schools.

Chávez and Cohen also make the confounding claim Allen was “involved in the New Orleans school reform efforts,” which has no basis in fact. It’s hard to see how Allen could have been involved, when she was running the Center for Education Reform over 1000 miles away in Washington, D.C. at the time.

When I raised this issue with Cohen on Twitter, she never responded. I guess I can understand the silence. I mean, who cares about facts when you’re selling readers a bill of goods?

4. They make up facts about New Orleans’ post-Katrina school reforms.

The truth continues to take a beating when Chávez and Cohen turn to the transformation of New Orleans public schools:

“Following Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Louisiana lawmakers granted the state’s so-called Recovery School District authority to take over underperforming New Orleans public schools. More than 100 schools were converted to charters, which are publicly funded and privately managed. Today, New Orleans is the only city in the nation to have a school system comprised entirely of charters.”

First of all, the Recovery School District didn’t turn more than 100 schools into charters. The city hasn’t even had 100 schools operating in the city at any one time since the storm. Second, as I’ve repeated ad nauseam over the past several years, there are a handful of traditional public schools still operating in New Orleans – i.e., the school system is not entirely comprised of charter schools.

5. They misrepresent Doug Harris’ research on the academic progress made in New Orleans.

Anyone who wants to debunk the success of New Orleans’ reforms has to deal with Doug Harris.

Harris, a professor of economics and director of the Education Research Alliance at Tulane University, co-authored what is considered to be the most comprehensive study of the progress made in the city’s schools since Hurricane Katrina.

What did his research find? Here’s how Harris summed it up in the pages of Education Next:

“For New Orleans, the news on average student outcomes is quite positive by just about any measure. The reforms seem to have moved the average student up by 0.2 to 0.4 standard deviations and boosted rates of high school graduation and college entry. We are not aware of any other districts that have made such large improvements in such a short time.”

In their piece, Chávez and Cohen acknowledge the progress in New Orleans, but misrepresent Harris’ conclusions, writing: “Harris’s research shows the city’s schools have improved over the last decade, in part by increasing school funding.” They also link to an interview with Harris in The 74, in an attempt to back their assertion that increased funding can explain the boost in academic achievement.

But once again, if you actually read the interview in The 74, you’ll find that Harris repeatedly discounts the role funding played in the improvements:

“It’s pretty unlikely that that’s the explanation…In fact, I think the increase in spending was almost certainly a necessary component of the reforms because to be able to attract people down here you needed to pay people well. And you needed to put in resources to get things going…I think probably every element of the reform package, including the change in spending, probably contributed in some fashion, but I think there’s not much reason to think that it was all about the money.”

Later in the interview, Harris reiterates this point, saying: “Again, I would say it’s true that putting more money into the schools does have some positive effect, but again looking at past research there’s not any reason to think that just doing those things would have generated this kind of an effect.”

In sum, Harris didn’t find that funding played a significant role in generating the academic gains seen in New Orleans, but Chávez and Cohen intentionally leave readers with the impression that it did.

6. They spin a conspiratorial narrative around bureaucratic inefficiency.

Chávez and Cohen spend the balance of their article enumerating all of the challenges that have prevented schools from reopening: bureaucratic red tape, an incompetent school inspection process, and a preexisting fiscal crisis that has hobbled the Puerto Rican government’s ability to respond. All the while, they suggest that the slow pace of reopening schools is actually part of a plan, hatched by government officials and others, that “foreshadows permanent closures and school privatization.”

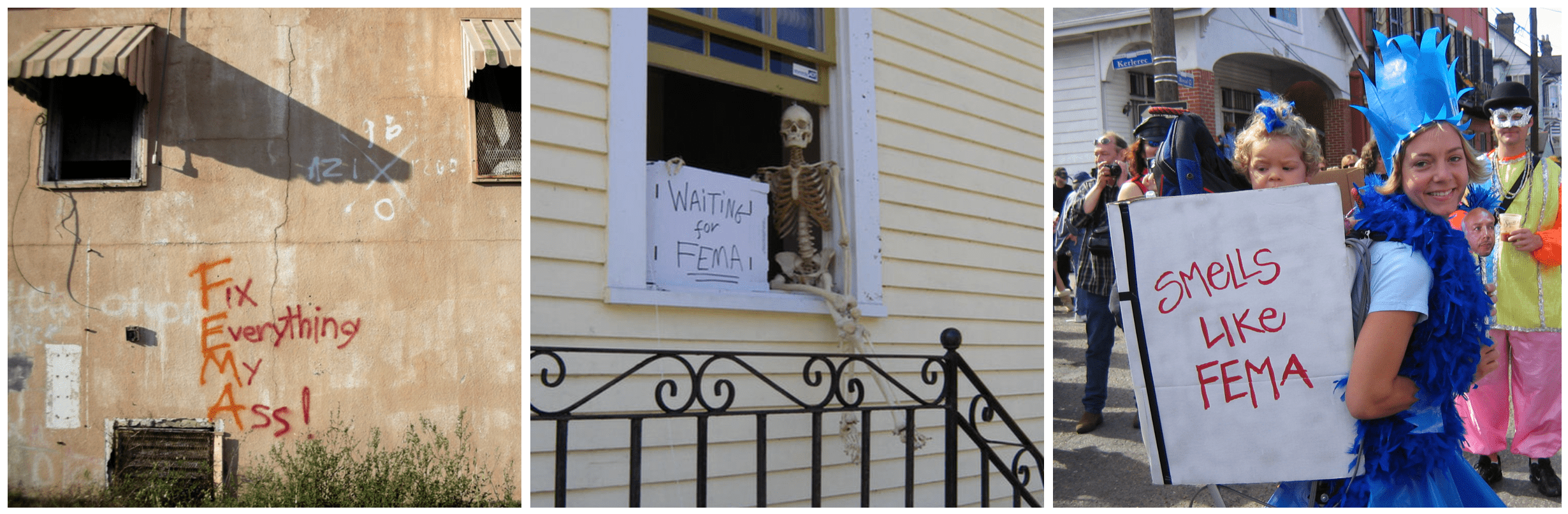

Yet for those of us who have actually experienced the aftermath of a major natural disaster, many of the complaints recounted by the authors sound strikingly familiar. Overwhelming and often competing needs, combined with the inefficiencies inherent in any large-scale government undertaking, mean that recovery efforts almost never move fast enough for those awaiting assistance.

After Hurricane Katrina, it was 13 weeks before the first public school in New Orleans reopened. In the case of Avery Alexander, a school in the Gentilly neighborhood of the city that was inundated by floodwaters during the storm, it took 12 years. Moreover, sluggish progress wasn’t unique to the school system. The Road Home Program, which was established to distribute federal funds to rebuild in areas impacted by Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, became a widely-reviled symbol of bureaucratic incompetence. It took years for Road Home to distribute more than $9 billion in grants to homeowners, a job that the program is still in the process of completing nearly 13 years after the storm.

None of this was the result of a conspiracy; it is the nature of the beast. It’s why we call events like Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Maria “disasters,” not “temporary inconveniences.” Chávez and Cohen’s attempt to spin a conspiratorial narrative around the plight of Puerto Rico’s public schools is irresponsible journalism, and it’s unhelpful to Hurricane Maria’s victims and unfair to officials who are scrambling to reopen schools as quickly as possible.

Except for the “progressive” media echo-chamber, here: bit.ly/2jldJEU; here: bit.ly/2jldU32; here: bit.ly/2jldKss; and here: bit.ly/2joNjSY

It’s worth noting that nobody else covering Puerto Rican school recovery has picked up this storyline. What does Harris say?